As the immigration debates have heated up in national politics recently, I've noticed a disturbing inhumanity in the language used to talk about these people. Let me emphasize the word we should use: people. I grew up in a small town in Colorado with a relatively high number of immigrants from Mexico in its population. My high school friends used to joke about them. For example, in an American History class our teacher started listing statistics. After she gave the number of illegal immigrants living in Western Colorado, one student whose family owned a fruit ranch near town interjected, "And half of 'em work for me!"

I had a few Mexican friends in high school, but for the most part stayed within the boundaries of the social segregation that was assumed in my hometown. After finishing school at the University of Colorado, though, I worked in a grocery store where half of my coworkers were Mexican, and many, if not most, of them were undocumented immigrants. Through the little bit of Spanish I learned in high school and the little bit of English they learned in the workplace, we talked, learned each others' stories, and came to share profound amounts of respect for each others' lives.

One of my supervisors had worked multiple fast food jobs, supporting a wife and kids on that thin wage for over a decade before finally getting the better job at our grocery store. Another man never learned much more English than "how can I help you" and "thank you very much", but was the hardest worker in the department and supported his wife and kids on that slim wage as well. Yet another man sought to continue climbing the ladder by applying for a promotion to "coffee-specialist", and even though he knew the job and the product inside and out, couldn't get the job because he didn't speak enough English.

Then came the month where the store did a "social security audit" verifying the SSNs of all their employees. Some numbers, of course, came back with problems. To protect the company, many of my friends were let go gracefully, given two months to find another job rather than being fired immediately. The man who was my trainer told me with tears in his eyes, "We all know this happens. It is sad. But we will find other jobs." He started looking for work in construction, others went to landscaping, and still others back to fast food. Their lives were uprooted, the relationships they'd built destroyed, and their years of hard work wiped away.

Seeing their pain and their struggle, their efforts to make a living, to provide for their children, and still have money to send back to family in Mexico, makes an impression. It is easy to talk about "illegal immigrants" the way the newspapers do. But when you're talking about mis amigos de esa tienda de abarottes, you realize they are real people.

Maybe that's why I got so upset with the "letters to the editor" in the newspapers today: A previous article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had pointed out that our European ancestors were illegal immigrants when the Mayflower washed ashore. An astute point. Today a local woman responded by writing "The [Native] culture was nearly destroyed in the process and thousands were killed through disease and a genocidal cleansing of land. . . . We should remember what happens to a people who don't [sic] control their borders to illegal immigration." Grammatical idiocy aside, this woman was insensitive enough to suggest that these people would bring disease and genocide to American culture! Another example: In a recent letter to the editor in my hometown newspaper, The Delta County Independent, a man likened immigrants to "a truckload of worms that has been progressively multiplying for decades."

Immigrants are not worms. They are not here to destroy our country. They are here because they are real people, seeking real ways to support their families, and trying to give their children a better life.

Now add to this basic human right the theological truths that we Christians believe: Abraham was an alien in a foreign land, as were the Israelites in Egypt and later in captivity in Babylon. In the Incarnation, Jesus Christ came as a foreigner to our level of humanity. Since Christ came, Christians have recognized that we are all aliens in a strange land, not at home until we arrive in heaven. We are, in St. Augustine's terms, the City of God dwelling within the City of Man. The letter of First Peter opens by calling us "strangers in the world". How can we, strangers in the world, blessed by the immigrations of our spiritual forbearers, deny justice to immigrants in our own nation today?

Think on the words of Malachi 3:5 (NIV): "So I will come near to you for judgment. I will be quick to testify against sorcerers, adulterers and perjurers, against those who defraud laborers of their wages, who oppress the widows and the fatherless, and deprive aliens of justice, but do not fear me," says the LORD Almighty.

Sunday, April 30, 2006

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

How God is Challenging My View of Academia (Poverty Part 3)

Thank you to my good friend Randy for the thoughtful comment in response to my last posting. Randy always has a way of speaking truth directly and forcefully, as seen in that comment. Recognizing that Jesus' words about riches, wealth, and the blessings of the poor have to do with a lot more than just spending our money wisely, it's time to ask, 'what else can we do to live up [or down] to what Jesus calls us to?'

Right now I'm reading a book by Shane Claiborne called The Irresistible Revolution. Shane is one of the founding members of a Philadelphia-based inner-city ministry/community called The Simple Way (http://www.thesimpleway.org). Fed up with the insulation of white Christian suburbia, Shane and some friends started going on regular trips to the inner city to have fellowship with a group of homeless families who lived in an abandoned church. Notice the choice of words there: they went for fellowship. The only mission they were on was to help protest the forced eviction of these families, but by taking on the literal role of Jesus in spending time in fellowship with them, they ended up falling in love with everyone there and making fellowship with those people a regular part of life. Eventually, they succeeded in preventing their eviction, with the help of several answers to prayer. The book conveys the power of the story much more than any summary I write can, so I certainly recommend it. What I can say, though, from having read a third of the book, is that I have been moved almost to tears several times while reading it because I see him doing ministry and making a difference in the world while I'm sitting here reading about it and "studying to do ministry".

Theology is important, no doubt, but there comes a point when scholarship insulates us from Jesus' calling in the same way that riches do. For example, take the difference between Matthew's version of the beatitudes and Luke's: "Blessed are the poor in spirit" vs. "Blessed are the poor." While I bet Jesus did mean to bless those who are grieving, mourning, and depressed, I've heard numerous people write off this blessing of the poor implying that Jesus only meant those who are poor in spirit. If we believe he only meant the poor in spirit, it's easy to start thinking that it's fine to be wealthy and miserly, all as long as we recognize that Christ meets us in our emotional sorrow.

That is, of course, a load of crap. But that's exactly what we feed ourselves when we start rationalizing away the brazenness of Jesus' message. This morning in Exegesis, Dr. Gagnon talked about how Jesus' words "Eat my flesh, drink my blood" were intentionally offensive because they were meant to call attention to his exclusive saving power. What do we do with that in church today? Call it symbolism and then forget what it symbolizes, namely the fact that Jesus' himself is The source of life.

So now I am left wishing that I was getting more real tangible experience in ministry right now - both to the poor in spirit and to the just plain poor. That is what my field education will provide in one aspect next year, but since I'll be working at a fairly well-off suburban church, I'll surely still be wrestling with these distinctions. Until then, I still admit that I'm not living up to Christ's calling here - I only pray that God will have mercy upon me until I actually do.

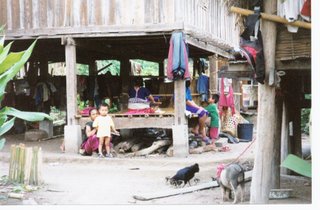

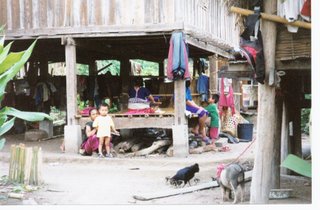

Parting thought: in the summer of 2002 I spent two months in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Living in the city, teaching English to college students, we met people who were mostly in the top ten percent of the country economically. Even so, we ate meals that cost only fifty cents each, standard fare for a full plate of rice, veggies, and some meat. Two weekends we traveled out to the rural villages to visit the people who work mostly as rice farmers. There the kids rarely get more than a third grade education and are lucky if they don't either go to jail for growing marijuana or become teenage prostitutes in the tourist areas in southern Thailand. Here's a picture of a typical family. We were some of the first Americans they saw and also some of the first Christians. What sort of message did we convey by showing up with all our digital cameras and multiple sets of clothes? Is that the Gospel? How could we have better represented Jesus to them?

Right now I'm reading a book by Shane Claiborne called The Irresistible Revolution. Shane is one of the founding members of a Philadelphia-based inner-city ministry/community called The Simple Way (http://www.thesimpleway.org). Fed up with the insulation of white Christian suburbia, Shane and some friends started going on regular trips to the inner city to have fellowship with a group of homeless families who lived in an abandoned church. Notice the choice of words there: they went for fellowship. The only mission they were on was to help protest the forced eviction of these families, but by taking on the literal role of Jesus in spending time in fellowship with them, they ended up falling in love with everyone there and making fellowship with those people a regular part of life. Eventually, they succeeded in preventing their eviction, with the help of several answers to prayer. The book conveys the power of the story much more than any summary I write can, so I certainly recommend it. What I can say, though, from having read a third of the book, is that I have been moved almost to tears several times while reading it because I see him doing ministry and making a difference in the world while I'm sitting here reading about it and "studying to do ministry".

Theology is important, no doubt, but there comes a point when scholarship insulates us from Jesus' calling in the same way that riches do. For example, take the difference between Matthew's version of the beatitudes and Luke's: "Blessed are the poor in spirit" vs. "Blessed are the poor." While I bet Jesus did mean to bless those who are grieving, mourning, and depressed, I've heard numerous people write off this blessing of the poor implying that Jesus only meant those who are poor in spirit. If we believe he only meant the poor in spirit, it's easy to start thinking that it's fine to be wealthy and miserly, all as long as we recognize that Christ meets us in our emotional sorrow.

That is, of course, a load of crap. But that's exactly what we feed ourselves when we start rationalizing away the brazenness of Jesus' message. This morning in Exegesis, Dr. Gagnon talked about how Jesus' words "Eat my flesh, drink my blood" were intentionally offensive because they were meant to call attention to his exclusive saving power. What do we do with that in church today? Call it symbolism and then forget what it symbolizes, namely the fact that Jesus' himself is The source of life.

So now I am left wishing that I was getting more real tangible experience in ministry right now - both to the poor in spirit and to the just plain poor. That is what my field education will provide in one aspect next year, but since I'll be working at a fairly well-off suburban church, I'll surely still be wrestling with these distinctions. Until then, I still admit that I'm not living up to Christ's calling here - I only pray that God will have mercy upon me until I actually do.

Parting thought: in the summer of 2002 I spent two months in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Living in the city, teaching English to college students, we met people who were mostly in the top ten percent of the country economically. Even so, we ate meals that cost only fifty cents each, standard fare for a full plate of rice, veggies, and some meat. Two weekends we traveled out to the rural villages to visit the people who work mostly as rice farmers. There the kids rarely get more than a third grade education and are lucky if they don't either go to jail for growing marijuana or become teenage prostitutes in the tourist areas in southern Thailand. Here's a picture of a typical family. We were some of the first Americans they saw and also some of the first Christians. What sort of message did we convey by showing up with all our digital cameras and multiple sets of clothes? Is that the Gospel? How could we have better represented Jesus to them?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)